What is Shari’ah?

The Path

by James S. Coates

As recent politics has put Islam and Islamic Shari’ah into the spotlight of public discourse, there is every reason you all should know about the topic of Shari’ah. A ton of misinformation has been circulating about Shari’ah and I’d suggest paying close attention to this post and ask questions if you don’t understand something or wish clarification.

What Does “Shari’ah” Mean?

The word “Shari’ah” literally means “an immense road leading to a flowing source of water.” It is literally the lifeblood of human social development, advancement, economics, enlightenment, culture and sophistication. Shari’ah guides us in every aspect of our lives such as our religion, culture, society and even as minute as personal hygiene.

There is no theocracy in Islam and as such Shari’ah as a whole is NOT God’s Law. Shari’ah consists of laws and interpretations codified by groups of ‘Ulamā (scholars/judges) in legal judgments called fatāwā (rulings or opinions, plural) or fatwā (singular).

These scholarly opinions are based in part on God’s revelations, the recordings of the hadith of Prophet Muhammad’s life compiled into canonical collections approximately 200–250 years after his death, modern social and cultural norms, and new technologies. Scholarly opinions on Shari’ah are based in areas of study among various Islamic schools of thought.

The Schools of Thought (Madhab)

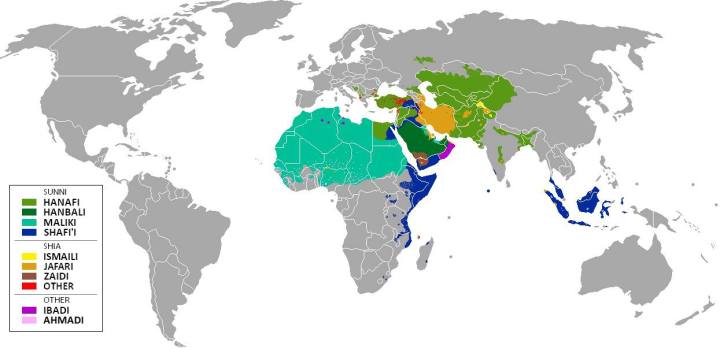

There are five main “Madhab” (pronounced “maḏhab”), or “Schools of Thought,” that are based on Imams (scholarly thinkers; teachers) who lived over 1,000 years ago. Each school interprets Islamic texts differently on various issues, and our modern scholars often refer to them to make decisions of Shari’ah and issue fatāwā (rulings/opinions). Some madhab are more predominant in some countries or regions than others.

Prime examples of differences between the madhab are Saudi Arabia (Sunni; Hanbali) and Iran (Shi’a; Ja’fari school), which are both Muslim but have developed hugely different religious structures and viewpoints. You can see that many countries also share the same madhab. Some Muslim communities in the West may have representations of all of the schools of thought, like the United States, United Kingdom and others. Muslims in the West are a melting pot of ideas, not just in secular society but also often in their religious communities.

These are the five main Madhab (Islamic Schools of Thought):

- Hanafi (Sunni)

- Maliki (Sunni)

- Shafi’i (Sunni)

- Hanbali (Sunni)

- Ja’fari (Shi’a)

How Shari’ah Differs by Region

Shari’ah on an issue in one group may not resemble the Shari’ah in another.

For example, the religious Shari’ah rulings of the Hanafi school (South Asia) say Muslims should pray with their hands folded, while the Maliki school (North Africa) says to pray with the arms by one’s side. Such rulings that differ can be on social, political and national differences as well.

An example of national differences might be Saudi Arabia (Hanbali), which may cut off someone’s hand for stealing, whereas Malaysia (Shafi’i) may simply put them in prison and give a hefty fine.

There is no single book of Shari’ah. You cannot go to a bookshop and ask for “The Book of Shari’ah” like you might the Bible or Qur’an or a volume of hadith. It isn’t there. Shari’ah is a “science of interpretation” by groups of people (‘Ulamā; scholars or judges) among the various schools of thought, which appear in fatāwā (rulings) that can be made on a regional, national, or local level—or even internationally agreed upon by consensus.

What Shari’ah Is NOT

Many Western antagonists like to pretend to know about Shari’ah and claim that the totality of Shari’ah is summed up in penal codes only acceptable in ancient times (such as the Roman Empire) but considered barbaric today. Shari’ah is made up of infinitely more than the few penal codes of certain repressive governments which they commonly point to today.

There are some “religious” aspects of Shari’ah that are internationally recognised as unchangeable, and some of those rulings you have already read in my previous posts, like “Islam is a 3 Dimensional Religion.” The very basic religious aspects of Shari’ah are agreed upon internationally by all Muslims and therefore unchangeable. To change or deny these religious ideals would be to deny Islam itself.

So, it is ridiculous for an antagonist to ask a Muslim if they deny Shari’ah as a measure of religious “moderation, reform or modernisation.” What part of it? Why would we deny “Shari’ah”?

For example, based on the Qur’an and hadith, according to all scholars of Islam worldwide, there are five pillars of Islam. The first pillar of Islam is the very basic entry point to becoming a Muslim (Shi’a and Sunni), and to become Muslim one must recite with wilful conviction the Shahadah (Confession of Faith). It is a requirement to be considered a Muslim by our peers. It is, therefore, part of the Shari’ah that a person must understand that there is no other god except the One God and Muhammad is the Last Messenger, and make a confession of their belief.

Shari’ah goes on to detail the other pillars (like Prayer, Fasting, Charity, and Pilgrimage) and the requirements for successfully fulfilling those requirements. How to pray, how many times to wash per day, requirements for giving charity, how to make pilgrimage—all are detailed by Shari’ah. Why would we be asked to deny these as a sign of “moderation or reform” when to do so makes us either a non-Muslim, like a non-Muslim, or prevents us from carrying out our Islamic duties?

To ask us to deny Shari’ah in light of this aspect is tantamount to asking a Christian to deny the articles of faith decided upon by their founding Church elders.

Shari’ah Courts and the Halakha Parallel

A Beth Din is a Jewish Halakha (Jewish Law) court that is set up in the United States, Europe, and many other countries. These Jewish courts make rulings (like fatwā) on behalf of Jewish communities in the United States. One such ruling is for Jewish communities to establish the Eruv (a physical public barrier that encircles a township or area predominantly Jewish, which allows certain religious rights to Jews) in predominantly Jewish neighbourhoods in non-Jewish countries. If one isn’t Jewish, he or she wouldn’t even know what it is even if it was pointed out to them, let alone know if one is present in the area they live in.

Despite the ancient Jewish practices (no longer practised) of stoning for various offences (Leviticus 20:10, 20:13; Deuteronomy 17:5), these Jewish courts in foreign countries (like the United States) function the same way Islamic law courts do in many non-Muslim countries around the world today. The implementation of Jewish law in a non-Jewish society has no bearing on non-Jews because Jews living in the West have modernised the portions of Jewish law that are not necessary to faith, like barbaric penal codes once acceptable 3,000 years ago. Like Jewish Halakha courts, Shari’ah courts operate in many countries, Muslim and non-Muslim (including Israel), leaving behind the ancient barbaric penal codes.

In fact, the debate about allowing Jewish law and Jewish Halakha courts, especially on issues like the Eruv to be implemented in Jewish communities in the US (and even in Europe), has brought the same concerns from the public as with Shari’ah courts. Despite antisemitic fear-mongering that has suggested in the past that the Jews were setting up a Jewish enclave in the US, it hasn’t created such issues like Jews stoning people in the streets, etc.

Shari’ah courts in a large number of countries (including many Western countries) are offered on an “opt-in” basis and make rulings between parties on issues of civil matters, divorce, or inheritance. Some Muslim countries refer marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance to Shari’ah courts by default, preferring un-Islamic (and barbaric) European colonial penal codes, laws, and cultural attitudes for the rest. In some dictatorships, where freedom to challenge the ruling party does not exist, these courts are used as a mouthpiece of the Monarchy or Dictatorship to make religious and other rulings often nonsensical to most ordinary Muslims and often contrary to Islam itself and a violation of human rights.

Modernisation and Reform

Shari’ah is a living, breathing legal system that is interpreted differently by different people, and only a small portion of it actually defines religious duties. It is imperative to note that over 90% of Shari’ah does not relate to religious life or practice and is “dynamic”—able to change based on time, place, the people, and technology. Social issues and criminal penal codes of Shari’ah could and should be modernised.

Often the only modernisation we see is among Western Muslim scholars and communities who live away from brutally repressive regimes. Under dictatorships that control Muslim populations today (like Saudi Arabia or Egypt), speaking publicly with new ideas that challenge, criticise, or question social norms, the law, and government could be a prison or death sentence. The state exerts absolute control over the religious establishment.

Freedom of expression in the West has cultivated a new generation of scholars free to propose new ideas on modernisation of Shari’ah that could not be done in nations like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, etc.

Conclusion

Shari’ah and Shari’ah courts are not something to be feared by Westerners. Islamic Shari’ah is not divine, monolithic, or rigid. Islam never allows compulsion in religion. Shari’ah is not imposed on non-Muslims, and Muslims may opt in or out.

Islamic Shari’ah is as compatible with Western law and way of life as Jewish Halakha. The key to a successful and integrated Shari’ah is to foster religious freedom for Muslims to debate ideas and partner with us to help us promote human rights in our communities here and around the world.

We will never “abandon our Shari’ah” because it defines and shapes our Aqeedah (Creed) and our religious practice. However, we can modernise, assimilate, or shed outdated interpretations of Shari’ah, such as penal codes designed for a place, a time, and a people that is far distant in the past.

It is not against Islam but rather consistent with Islam, from its inception to its Golden Age, to replace old ideas with new modern values suited for the times and place we live in.

“O ye who believe! Stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to Allah, even as against yourselves, or your parents, or your kin, and whether it be (against) rich or poor: for Allah can best protect both. Follow not the lusts (of your hearts), lest ye swerve, and if ye distort (justice) or decline to do justice, verily Allah is well-acquainted with all that ye do.” — Qur’an 4:135

Article by BrJimC © 2016, revised 2026