Bismillah Ar-Rahman Ir-Raheem (In the Name of Allah, The Most Merciful, The Most Beneficent)

by James S. Coates

Introduction

“And hold firmly to the rope of Allah all together and do not become divided. And remember the favour of Allah upon you—when you were enemies and He brought your hearts together and you became, by His favour, brothers.” — Qur’an 3:103

I have worked with a number of major Muslim organisations and movements in America. I have organised events with them, raised funds for them, defended them in the media, and built bridges between them. I have also been praised by them, shut out by them, and ultimately expelled by some of them. I have seen the best of our community and the worst.

I originally wrote this article in 2007, when these experiences were fresh and the wounds still raw. I have since stepped back from active involvement in the organised Muslim community in America. I am revisiting and revising this piece now because, while some things may have changed in the intervening years, structural divisions along ethnic, tribal, and movement lines do not disappear quickly. If even some of what I witnessed remains true, then naming it is still necessary. I offer this not as a definitive account of how things are today, but as a testimony of what I experienced and an invitation for others to reflect honestly on whether these patterns persist in their own communities.

What follows is an account of the divisions I have witnessed within the American Muslim community—divisions along ethnic, national, tribal, and doctrinal lines. I write this not to condemn but to name what many of us know but few will say openly. If we cannot name a problem, we cannot solve it.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said in his final sermon:

“All mankind is from Adam and Eve. An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab, nor does a non-Arab have any superiority over an Arab; a white has no superiority over a black, nor does a black have any superiority over a white—except by piety and good action.”

We profess this. We must ask ourselves whether we live it.

The Divisions

The topics I address in this article are:

- Immigrant versus Indigenous American Muslims (not new converts)

- Immigrant versus American Muslim Converts

- Immigrants versus their American-born Children (2nd generation)

- Jamaat-e-Islami versus Muslim League

- Ikhwan versus other Movements

- Salafi versus other Madhabs (schools of thought)

- Tablighi Jamaat versus other Movements

- Summary of Alliances and Divisions

Please bear with me as I explore and explain these divisions. Some of what follows will be uncomfortable. But the Prophet (peace be upon him) told us that the best jihad is a word of truth spoken to an unjust ruler. Sometimes the injustice is within our own house.

1. Immigrant versus Indigenous American Muslims

In this divide, you have approximately 30% of the Muslims in America being indigenous to the Black American community—descendants of former slaves taken from Islamic areas of Africa. Many of them are in poor communities. Some are Muslims from birth through family lineage; others came through the Nation of Islam and, like Malcolm X, realised it was not true Islam, left, and joined the broader Muslim community. They form their own communities and sometimes intermingle with the general Muslim community at large.

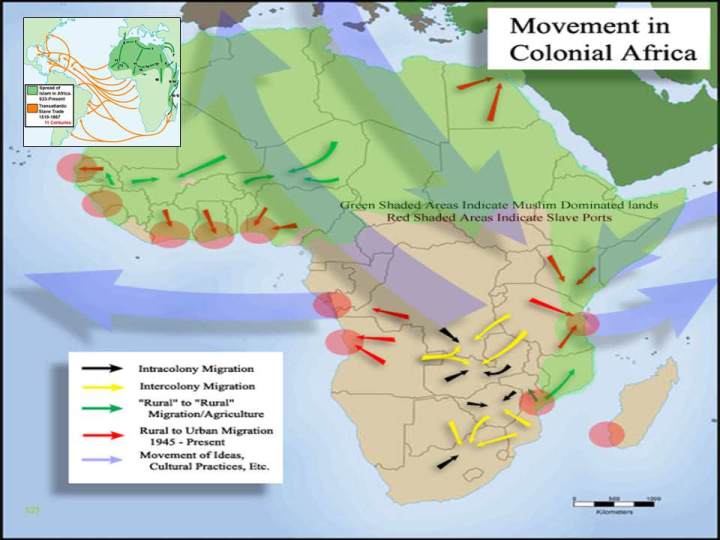

On the other side, you have foreign-born Muslims. Other than the approximately 2% of whites, Hispanics, and others who are indigenous or convert to Islam, the first-generation immigrant population makes up roughly 68% of Islam in America. Many came in the 1940s fleeing Communism in former Soviet bloc countries. Pakistanis came from South Asia fleeing famine and drought. In 1948 and 1967, the wars with Israel brought both Christian and Muslim Palestinians. The mid-1960s marked a significant increase of Muslim immigration from Pakistan, Turkey, Indonesia, and other Eastern and Arab countries, coming with the oil and other industries, seeking education or jobs.

What I Witnessed

I have seen a severe divide between indigenous Black American Muslims and immigrants—to the extent that they have formed entirely separate communities. When I was raising money for ICNA to build the Freeman Center in Houston, which is in a Black American community, I heard immigrant Muslims question why I was doing such a deed. One said, “Every time you see a black, they have their hand out.” It didn’t matter that the area had Muslims in it; they were indigenous former slaves and lumped into the larger stereotype of Blacks in America.

In the 1960s and 70s, Black Muslim communities, joining the fight for civil rights, attempted to ally with first-generation Muslims. According to one Imam in Houston, the first-generation community viewed Black Muslims as having serious doctrinal issues. Instead of attempting to correct such issues, they ostracised the Black indigenous Muslims and treated them as apostates—to the extent that Black Muslims had to form their own masajid (mosques).

At the Texas Dawah Conference 2003, a Canadian-born Islamic scholar told the conference that it was good they got together, but all he saw was Pakistani and Arab faces. He urged them to get indigenous Black American Muslims represented as an active part of the conference since they represent such a significant portion of the Islamic community in America.

So at the Texas Dawah Conference 2004, I attempted to heal this rift. I invited the Black indigenous Muslim community to be a part of the conference. The Black leaders I spoke to were eager to participate, even in a small way, and repeated to me the need to heal this rift—but were concerned with how the immigrant community would treat them.

When I spoke to the organisers, it was initially met with cautious optimism. The concern was what the Black Muslims would be “teaching” at the conference and whether it was sound doctrine. So it went through the ranks, and the main organiser dispatched an email putting a dead stop to it on the basis that the indigenous Blacks’ doctrine was not sound—even though they acknowledged the Black indigenous Muslims were Muslims in need of education in Islam. Instead of working with them in a way that addressed their concerns, they completely shut them out of the conference. There was no indigenous American Muslim representation on an official basis, and virtually none showed up to attend.

The conference is billed to the community as a unifying force to bring organisations together. It failed to bridge the gap between indigenous American Muslims (30% of the community) and the immigrants (the organisations represented at the conference).

The divide between immigrant and indigenous Black American Muslims is deeply felt and will not be healed soon, since the immigrant community continually views them as beggars, shuts them out, and ostracises them.

2. Immigrant versus American Muslim Converts

According to the majority of Islamic scholars, one of the primary reasons Muslims have to live in a non-Muslim nation is for the purpose of dawah (propagation of Islam)—making converts. Yet making converts in a non-Muslim land creates a paradox for immigrant Muslims, and the experience is often frustrating for new converts.

One of the best moments in a convert’s life is first becoming Muslim. It is a sense of freedom, belonging to a greater community, brotherhood, and guidance. As converts grow in their new faith, they acquire knowledge of Islam from the immigrant perspective, are inundated with an array of political ideas (typically anti-Western), and struggle to understand the inner workings of the faith, various cultures, and the Arabic language.

The Language and Cultural Barrier

When I became involved in the Islamic community, I struggled for clear answers from knowledgeable Muslims because of the language barrier. Most of the Imams and scholars in the West are not American, or at least were born in another country and immigrated to America, even if they acquired citizenship. They are ESL (English as a second language) people from Egypt, Pakistan, or elsewhere. The same applies for the majority of Muslims in the masajid. They speak English at an academic level but do not understand street lingo or common American English. They also have little or no connection to the plight of Americans, our history, or how our country operates outside of what they know from back home.

The prominent undercurrent of ideology in the masajid reflects people who come from countries with brutal regimes, where law enforcement agencies are arms of dictatorships, where there is constant turmoil and often poverty. Attitudes towards the West are dominant, and to oppose these attitudes publicly can put one’s conversion in question. First-generation Muslims in the masajid are on constant lookout for infiltrators, and new converts feel heavy pressure to go along with the flow and view anti-Western politics as Islamic, even when it is not.

One of the first things that happened to me was that I was questioned about my view of the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. Even though I somewhat agreed with the stance of most Muslims, I didn’t convert to Islam for such ideology. I wasn’t at the meeting for a contemporary political discussion but to learn about Islam. As time went on, constant inundation with various Muslims’ political ideology made me more comfortable with radically different ideologies since it seemed to be the norm. Eventually, I grew out of that. However, a large number of converts do not.

The “Lap Dog” Experience

New converts are seen by foreign-born Muslims as people who can help the plight of Islam among non-Muslims much easier than themselves. However, when it comes to matters of Islam, politics, or social integration, first-generation Muslims often view converts—no matter how educated or how long they have been Muslim—as uneducated in Islam and having little bearing on the direction of the community and its organisations. For example, as a Muslim now for 28 years, I am still told that I know nothing about Islam when it suits their point of view.

Converts often feel similar to how I felt since 9/11. When they needed us after 9/11, they thrust us in the public eye to defend Islam and put a clean, sanitised face on Islam and Muslims. However, when it comes to listening to our opinion on the direction of the communities, Islamic thought on issues regarding the religion, and running for or holding office in the organisation, they will not have it. It is extremely rare for an American Muslim to hold leadership positions—I know of only one case where a Black American Muslim was voted into local office as President of ICNA’s Houston Chapter, and that wasn’t without bitter rivalry.

I, and others I associated with, felt like a lap dog. I worked feverishly night and day, sacrificing time with my family while they enjoyed theirs, and it amounted to nothing. They love to pat you on the head and sing your praises when you’re in public making them look good, but they don’t want you to say anything meaningful or try to be a significant part of their immigrant-controlled organisations.

First-generation Muslims will profess that we are all equal in the sight of Allah. But they almost never relinquish control of their organisations to an American convert (unless they feel they can control him), nor are they hiring American Muslim scholars in the masajid. They will almost always hire scholars who are not American, and they will not allow many qualified American Muslims to give sermons in the masajid for Friday prayers or other events.

Double Standards

Furthermore, there is a pattern of double-speak. They condemn terrorists or extremists breaking our laws while supporting them through their actions. If a convert supports an immigrant, then great—but if you disagree, or speak to law enforcement about criminal activity in the community, they will brand you an infiltrator and claim you’re not really Muslim. Blood is thicker than water; it becomes tribal. They won’t play fair, following through on the teachings of Islam they instilled in you. They won’t give you opportunity to explain yourself. Instead, they will expel you from their organisations even though your work is what earned them a trusted name. If that is not all, they will post your name and photos everywhere in an attempt to threaten and intimidate you. It is exactly what happened to me.

The last I checked, Islam stood for justice, not lawlessness, and didn’t require us to protect lawbreakers simply because they are Muslims, nor on the basis they are from Pakistan, etc. It certainly forbids Muslims from threatening other Muslims.

The immigrant and convert divide is stark. It is not only different cultures meeting but different approaches and resolutions to life’s issues. It’s a different approach to Islam since most American Muslims are proud to be American and Muslim, while many who immigrated are here to benefit from America, their minds on returning home at some unknown point in the future, but not to become American or integrate into American society to show non-Muslims that we are not all terrorists. It’s almost as if things go south, they have somewhere else to go, but American Muslim converts do not have such options. It makes for a different worldview between us.

Where the Energy Goes

When I put on a Justice For Allah Rally in 2003, speaking out against Israeli atrocities against Muslims in Palestine, it was easy to get 400 people to show up and voice their opinion. But trying to get them to feed the homeless on a regular basis, give clothes to the needy, have a friendly meet with their neighbours, or do dawah work was worse than pulling teeth.

Save one instance that deserves merit: when they found out it would benefit them publicly to help the Hurricane Katrina evacuees, they came together and did some good work. But it wasn’t without some of them trying to take all the credit in front of the cameras from the others, and private threats from one organisation to the next. If it wasn’t for a Christian interfaith organisation (that I had a chance to work for as a Muslim liaison) that helped get past the petty rivalries, they would never have pulled it off.

3. Immigrants versus their American-born Children (2nd Generation)

A large portion of first-generation Muslims in the United States are not citizens and seem to have the intention of returning to their home countries after they receive their education or retirement. However, it is a common joke—and I heard this at the Texas Dawah Conference 2004—that immigrants come with the intention of returning to their countries, but every year they postpone it. Then, after years of delay, when they finally tell their kids (who were born and raised in the USA) that they want to move the family back home, their kids question the sanity of such an idea: why would they leave America when this is the only home they’ve ever known?

Cultural Clashes

Cultural values of the immigrant population are in stark contrast to those of their American-born children. The elder generation tends to adhere to archaic cultural values based from their home countries. An example of this is marriage. Many immigrant families have an understanding that they will bring their children back to Pakistan (or wherever they are from) to find a suitable spouse (oftentimes cousins) when their children are old enough. Furthermore, they tend to want to make the choice for their kids without any significant input or protest.

When presented with such an idea, the children typically dread such a concept. Their children, after all, grew up in America where this is not a cultural norm. Islamically, the children are right to consult the parents, but in Islam the parents are not the deciding factor on whom they marry. Islam encourages ethnic mixing and the freedom for children to choose their own spouse on the basis of piety.

The Generational Divide in the Masajid

Another divide is in the religious community. Second-generation children tend to grow up with Western values which allow for more free thought, and these are infused into their Islamic understanding of the world and the community. They are young, idealistic, and have a lot of energy. When children of immigrant Muslims grow old enough, they see the flaws in the community their immigrant fathers (“Uncles” they call them) are running—how it is run and how Islam is being taught—and have a strong desire to change it. They are frustrated when they see the community politics, backstabbing, underhanded behaviour, and when they are shut out of any meaningful effect or ability to hold office.

This division is very much like that of the division between converts and immigrant Muslims, except that the second-generation Muslim children are still very much united by ethnicity and their parents’ tribal affiliations that American Muslim converts do not have.

Muslim communities are seriously stifled from progress and growth due to the elder generation of first-generation Muslims’ power struggles, tribal warfare, false accusations, politicking to get rid of moderate Imams and scholars or those they just don’t like, seizure of power, destruction of property, and refusal to allow fresh blood into control of the governing and consultative bodies and the presidencies.

4. Jamaat-e-Islami versus Muslim League

An underlying divide among Pakistani immigrants in America, not evident to the general public, is a political divide originating in Pakistan. Jamaat-e-Islami is a religious and political movement in Pakistan that elevates and follows the teachings of Syed Maududi. It is a movement that aims to get back to the basics of Islam and has representation in the Pakistani National Assembly.

The Jamaat propagates its ideology worldwide in the masajid and founds organisations in various countries that reflect its ideology. In the United States and Canada, they have founded the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA) and ICNA Relief. Since ICNA cannot operate as a political party in the USA and Canada, they have founded the movement as a religious organisation whose purpose is to propagate Islam according to its movement’s ideology.

According to an ICNA official that I spoke to privately on this issue, the Muslim League is the “other” party. They are the ruling class that originally received the handoff of power from the British after the ending of colonial rule and the subsequent founding of the nation of Pakistan. They are seen by Jamaat supporters as puppets of the West and a corruption of Islam in Pakistan.

The divide between these two groups is kept very private, but it is very evident in the Islamic community in America when one looks at the community politics in the masajid. This barrier is very real and originates long before the two parties immigrated to America.

5. Ikhwan versus other Movements

The Ikhwan are highly active people who engage in many facets of society. Like other movements, they propagate their ideology around the world in the masajid, but in addition they also propagate among Muslims in universities. The Ikhwan can be cautious about public statements regarding some of their ideology due to their Egyptian history of government persecution. However, they have aspirations of being politically active in the West and will engage in society and attempt to affect change positively through the political process.

In the United States, they have founded their organisation as the Muslim American Society (MAS), and in universities and schools they have founded the Muslim Students’ Association (MSA). They have also founded a political organisation called MAS Freedom Foundation and a worldwide relief organisation called Islamic Relief.

Working with the Ikhwan

The real division between Ikhwan and other movements in the American Islamic community is that the Ikhwan have a strong desire to be seen publicly and to be looked at by the Islamic community as being effective and moderate. However, in my experience, some can act as bullies in the community, pressuring other organisations to let them take the lead or take credit for joint efforts. Any event they are involved with becomes a struggle for other organisations to control, as well as a struggle over who actually is recognised in the end for their work and organisation. So other organisations find it difficult to work with them.

6. Salafi versus other Madhabs (Schools of Thought)

Among the various groups in the masajid are the Salafi. The Salafi movement traces its methodology to the Salaf—the first three generations of Muslims (the Companions, the Successors, and those who followed them). Opponents of the movement often call them “Wahhabi” after Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a reformer in 18th-century Arabia, though Salafis themselves rarely use this term and generally reject it as a label designed to malign their movement.

The movement was founded during a time when Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula had distorted Islam to the point of reverting to old pagan ways. Its aim was to bring people back to Islam through sound teaching based on Qur’an, Sunnah, and the understanding of the Salaf. Eventually, the movement formed an alliance with the Saudi government, and it is traditionally associated with the Hanbali school of fiqh (jurisprudence).

Like other movements in Islam, Salafi teachings are propagated around the world in the masajid. It is among the most strict and literalist forms of Sunni Islam. It is not uncommon for Salafis to oppose becoming involved in the political process of non-Muslim countries, viewing it as a system of kufr (disbelief). So the only way many will engage politically is if an Islamic system of government is already established. Some Salafis view their religious methodology as superior to others, to the extent that they will pronounce takfir on other Muslims (declare them apostates) not part of their group—though this practice is condemned by mainstream Salafi scholars.

The Salafi are not recognised as a separate school of thought by mainstream Sunni Muslims, who recognise only four schools (Maliki, Hanbali, Hanafi, and Shafi’i). However, their strict methodology puts them in contrast with the general community at large. They are often very vocal in the masjid and propagate their way aggressively, which creates division.

7. Tablighi Jamaat versus other Movements

The Tablighi Jamaat is a movement whose origins are in India, begun during a time when Muslims were reverting to the ways of Hinduism. The purpose of the Tabligh is to do dawah (propagate Islam) among Muslims and call them back to Islam. It is their practice to leave behind family and friends occasionally for an extended period of time to travel from community to community to encourage people to adhere to Islam and recruit into their ranks. They typically just show up in an unsuspecting community, make friends, and stay with people they meet who feed and support them for the duration of their stay, or with other Tablighis. Sometimes they stay in the masajid themselves.

The Tabligh operate in the US and Canada as their own organisation with a hierarchy apart from most institutions. There is criticism among the general community that their teachings are from books containing weak hadith (teachings of the Prophet that cannot be confirmed as authentic) and thus are somewhat inaccurate. They are often not allowed to operate within the masajid without consent and sometimes without prior approval for what they will be teaching or books used in their sermons. Some communities have restricted them due to their transient lifestyles.

It is not uncommon for a new recruit of the Tabligh to be encouraged to abruptly leave their home to go on a two- or three-week mission to another community to propagate Islam (according to the Tabligh) or learn more about Islam and the Tablighi way.

The movement is rather large and largely made up of Indian and Pakistani members. However, the movement has gained considerable ground in the Black American Muslim community.

Summary of Alliances and Divisions

Ethnic and Generational Divisions:

- First-generation Muslims versus indigenous American Muslims, converts, and their 2nd-generation children born and raised in America

- Second-generation ethnic children of first-generation Muslims group together and often separate on ethnic lines from indigenous American Muslims and converts

- Indigenous Black American Muslims follow the natural segregation lines in society when it comes to integration with other groups

Movement Alliances and Rivalries:

- Jamaat-e-Islami (ICNA, ICNA Relief) is a religious movement allied with the Ikhwan in the USA (MAS). The Jamaat is opposed to the group representing the Muslim League in Pakistan, who have formed cultural centres to promote Pakistani culture rather than the religion of Islam.

- The Ikhwan (MAS, MSA, MAS Freedom Foundation, Islamic Relief) tends to go it alone among all of the groups. Other movements are in constant struggle over how MAS controls, assimilates, and takes over their events. MAS (Ikhwan based in Egypt from the teachings of Syed Qutub) and ICNA (based in Pakistan from the teachings of Syed Maududi) have discussed merging their two movements in the United States and Canada. However, due to the stark nature of both movements, their cultures, and differing levels of Islamic knowledge, this has proven very difficult.

- The Salafi movement is relatively isolationist while at the same time not ashamed to publicly and vocally oppose other movements. They are often academic scholars but can lack tact and the ability to deal with people without giving offence.

- The Tablighi Jamaat operates largely independently, focused on internal Muslim revival rather than engagement with broader society or other movements.

A Path Forward

I have worked with all of these groups and know people and scholars from all of them. These findings are mine, based on my personal experience, talking with organisational officials, common folks, and scholars.

I write this not to condemn any group but to name what we all know exists. The Prophet (peace be upon him) said:

“The believers in their mutual kindness, compassion, and sympathy are just like one body. When one limb suffers, the whole body responds to it with wakefulness and fever.” — Sahih Muslim

We are not acting like one body. We are acting like competing tribes, each convinced of our own superiority, each protecting our own power, each suspicious of the other.

What would it look like to actually change?

- For first-generation communities: Include indigenous Black American Muslims and converts in leadership—not as tokens, but as equals. Hire American-born scholars. Listen to the perspectives of those who grew up here.

- For converts: Be patient but persistent. Document what you experience. Write books and articles on your experiences, they are valuable. Build alliances with second-generation Muslims who share your frustrations.

- For second-generation Muslims: You are the bridge. You understand both worlds. Use that position to push for change from within.

- For all movements: Cooperate on common causes without needing to control or take credit. The goal is the pleasure of Allah, not the reputation of your organisation.

- For all of us: Remember that the person you are dismissing, ostracising, or threatening is your brother or sister in Islam. On the Day of Judgement, our tribal affiliations and organisational memberships will mean nothing.

“O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you.” — Qur’an 49:13

May Allah help us to see past our divisions and become united for good causes. May Allah help us to forbid the evil and promote the good. May Allah forgive us where we have wronged each other, and may He guide us to be one Ummah as He commanded.

Ameen.

Article by BrJimC © 2007, revised 2026

You must be logged in to post a comment.